E.M. Forster’s

ALEXANDRIA: A HISTORY AND GUIDE

Excerpts

from CLEOPATRA

Back in Alexandria again, [Cleopatra] watched the second duel—that between Mark Antony and

Caesar’s murderers. She helped neither party, and when Antony won he summoned her. She came, not

in a carpet but in a gilded barge, and her life henceforward belongs less to history than to poetry.

Voluptuous but watchful, she treated her new lover as she had treated her old. She never bored him,

and since grossness means monotony she sharpened his mind to those more delicate delights, where

sense verges into spirit. Her infinite variety lay in that. She was the last of a secluded and subtle race,

she was a flower that Alexandria had taken three hundred years to produce and that eternity cannot

wither…

Back to the top.

from LITERATURE

History is too much an affair of armies and kings. Theocritus’ Fifteenth Idyll corrects the error. Only

through literature can the past be recovered, and here Theocritus—wielding the double spell of realism and

of poetry—has evoked an entire city from the dead and filled its streets with men. As Praxinoe remarks of

the draperies ‘Why the figures seem to rise and move about, they are not patterns, they are alive.’

Back to the top.

from THE ARAB CONQUEST (641)

The following year Amr entered in triumph through the Gate of the Sun that closed the eastern end of the

Canopic Way. Little had been ruined so far. Colonnades of marble stretched before him, the Tomb of

Alexander rose to his left, the Pharos to his right. His sensitive and generous soul may have been moved, but

the message he sent to the Caliph in Arabia is sufficiently prosaic. He writes: ‘I have taken a city of which I

can only say that it contains 4,000 palaces, 4,000 baths, 400 theatres, 1,200 greengrocers and 40,000 Jews.’ And

the Caliph received the news with equal calm, merely rewarding the messenger with a meal of bread and oil

and a few dates. There was nothing studied in this indifference. The Arabs could not realise the value of

their prize. They knew that Allah had given them a large and strong city. They could not know that there was

no other like it in the world, that the science of Greece had planned it, that it had been the intellectual

birthplace of Christianity. Legends of a dim Alexander, a dimmer Cleopatra, might move in their minds, but

they had not the historical sense, they could never realise what had happened on this spot nor how

inevitably the city of the double harbour should have arisen between the lake and the sea. And so though

they had no intention of destroying her, they destroyed her as a child might a watch. She never functioned

again for over 1,000 years.

Back to the top.

from ISLAM

We have now seen Alexandria handle one after another the systems that entered her walls. The ancient religion

of the Hebrews, the philosophy of Plato, the new faith out of Galilee—taking each in turn she has left her

impress upon it, and extracted some answer to her question, ‘How can the human be linked to the divine?’

It may be argued that this question must be asked by all who have the religious sense, and that there is nothing

specifically Alexandrian about it. But no; the question need not be asked; indeed, it was never asked by Islam,

by the faith that swept the city physically and spiritually into the sea. ‘There is no God but God, and

Mohammed is the Prophet of God,’ says Islam, proclaiming the needlessness of a mediator; the man Mohammed

has been chosen to tell us what God is like and what he wishes, and therein ends all machinery, leaving us to

face our Creator. We face him as a God of power, who may temper his justice with mercy, but who does not

stoop to the weakness of Love, and we are well content that, being powerful, he shall be far away. That old

dilemma, that God ought at the same time to be far away and yet close at hand, cannot occur to an

orthodox Mohammedan. It occurs to those who require God to be loving as well as powerful, to Christianity

and its kindred growths, and it is the weakness and the strength of Alexandria to have solved it by the

conception of a link. Her weakness: because she had always to be shifting the link up and down—if she got

the link too near to God, it became too far from man, and vice versa. Her strength: because she did cling to the

idea of Love, and much philosophic absurdity—much theological aridity—must be pardoned to those who

maintain that the best thing on earth is likely to be the best in heaven.

Back to the top.

from NAPOLEON (1798-1801)

On July 1st 1798 the inhabitants of the obscure town saw that the deserted sea was covered with an

immense fleet. Three hundred sailing ships came out from the west to anchor off Marabout Island, men

disembarked all night and by the middle of next day 5,000 French soldiers under Napoleon had occupied

the place. They were part of a larger force, and had come under the pretence of helping Turkey, against

whom Egypt was then having one of her feeble and periodic revolts. The future Emperor was still a mere

general of the French Republic, but already an influence on politics, and this expedition was his own plan.

He was in love with the East just then: The romance of the Nile valley had touched his imagination, and

he knew the way led to an even greater romance—India. At war with England, he saw himself gaining at

England’s expense an Oriental realm and reviving the power of Alexander the Great. In him, as in Mark

Antony, Alexandria nourished imperial dreams. The expedition failed but its memory remained with him:

he had touched the East, nursery of kings.

Back to the top.

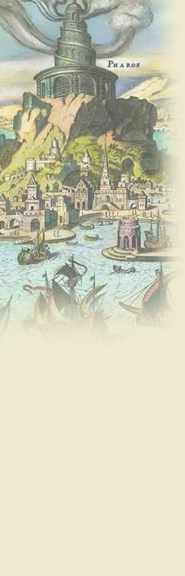

from PHAROS

The lighthouse took its name from Pharos Island (hence the French ‘phare’ and the Italian ‘faro’).

No doubt it entered into Alexander the Great’s scheme for his maritime capital, but the work was not

done till the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphus. Probable date of dedication: B.C. 279, when the king held a

festival to commemorate his parents. Architect: Sostratus, an Asiatic Greek. The sensation it caused was

tremendous. It appealed both to the sense of beauty and to the taste for science—an appeal typical of the

age. Poets and engineers combined to praise it. Just as the Parthenon had been identified with Athens

and St. Peter’s was to be identified with Rome, so, to the imagination of contemporaries, the Pharos

became Alexandria and Alexandria became the Pharos. Never, in the history of architecture, has a secular

building been thus worshipped and taken on a spiritual life of its own. It beaconed to the imagination, not

only to ships at sea, and long after its light was extinguished memories of it glowed in the minds of men.

Back to the top.

|