E.M. Forster’s

ALEXANDRIA: A HISTORY AND A GUIDE

THE FONTHILL EDITION

Back in Alexandria again, [Cleopatra] watched the second duel—that between Mark Antony and Caesar’s murderers. She helped neither party, and when Antony won he summoned her... She came,

not in a carpet but in a gilded barge, and her life henceforward belongs less to history than to poetry...

Voluptuous but watchful, she treated her new lover as she had treated her old. She never bored him,

and since grossness means monotony she sharpened his mind to those more delicate delights, where

sense verges into spirit. Her infinite variety lay in that. She was the last of a secluded and subtle race,

she was a flower that Alexandria had taken three hundred years to produce and that eternity cannot

wither. Back in Alexandria again, [Cleopatra] watched the second duel—that between Mark Antony and Caesar’s murderers. She helped neither party, and when Antony won he summoned her... She came,

not in a carpet but in a gilded barge, and her life henceforward belongs less to history than to poetry...

Voluptuous but watchful, she treated her new lover as she had treated her old. She never bored him,

and since grossness means monotony she sharpened his mind to those more delicate delights, where

sense verges into spirit. Her infinite variety lay in that. She was the last of a secluded and subtle race,

she was a flower that Alexandria had taken three hundred years to produce and that eternity cannot

wither.

from ALEXANDRIA: A HISTORY AND A GUIDE

Widely regarded as “the best guidebook ever written” E. M. Forster’s

ALEXANDRIA remains one of the most rare and least explored of his works—an

evocative, informative exploration of that most fabled, exotic and elusive of all the

world’s cities.

Now for the first time ever Forster’s ALEXANDRIA appears in eBook format, and

the release of the Fonthill Edition in 2012 coincides with the book’s 90th anniversary.

Forster spent several of the most influential years of his life in Alexandria—that ever

complex, ever-enduring, multi-faceted ancient/modern city founded by Alexander

the Great more than two millennia ago. Perhaps the world’s first truly cosmopolitan

city, Alexandria remains forever intriguing. More than either a History or a Guide

Forster’s ALEXANDRIA, as Lawrence Durrell noted, is an exquisite labour of love.

FOREWORD

FONTHILL PRESS LLC is pleased to release E. M. Forster’s overlooked and under-read

1922 classic Alexandria: A History and a Guide. This is the first eBook edition of Mr Forster’s

Alexandria, and its release in 2012 coincides with the book’s 90th anniversary.

As we might assume, much has changed in Alexandria during those 90 years; streets

bearing French names at that time are now in Arabic; tramlines have disappeared and the

Greco-Roman Museum has wings and alcoves that Mr Forster may certainly have enjoyed

wandering through, recording his thoughts, scribbling his notes. A list of Alexandrian

changes could go on for pages. As Robert Tracey pointed out in 1961: as a travel guide,

strictly speaking, much of the information here is “obsolete.” And to say the least, the

ensuing half century has scarcely altered that fact—and yet Alexandria clings to its many

charms and to an essential spirit whose relevance time and change and revolution can

scarcely alter or diminish; indeed, one can say this little gem still lends pleasurable reading for

the traveller, whether one finds oneself reading these pages in the vicinity of the “Soma”—

the vanished tomb of Alexander the Great, an ancient site of pilgrimage for common folk

and Caesars alike—or snuggled into a cosy fireside chair, an ocean and a continent or two

away from the brilliant Mediterranean sun.

The quirks and eccentricities in Mr Forster’s 1922 Alexandria abide in FONTHILL’S

digital offering; nevertheless, here and there, now and again, we have chosen to correct this

or that, for instance: the spelling of the surname of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which hitherto

suffered from a missing ‘s’ (whether the first or second, we could not tell). Things of that

sort. Nevertheless, we have done what we can to heed and duly note Mr Forster’s stinging

reproach to grammarians (editors and proofreaders?) everywhere: “Grammar is a valuable

subject, but also a dangerous one, for it naturally attracts pedants and schoolmasters and all who

think that Literature is an affair of rules.”

Point taken, Mr Forster.

We have added a few illustrations that we think the author might have approved and

used, had they been available; most he did use in 1922 have been used anew, albeit digitally

enhanced. At the end of most sections in the ‘Guide’ you will find a brief listing of place

names, which Mr Forster accompanied with page numbers directing his readers to sections

in the ‘History,’ thus linking the two. Pages numbers are for printed books; in digital format,

names and subjects can be searched electronically, and this is especially easy in

FONTHILL’s enhanced digital edition.

Finally, we are deeply grateful to Dr David Cowart, distinguished scholar and author of

Thomas Pynchon and the Dark Passages of History, etc., for graciously according FONTHILL the

privilege to publish “Where Sense Verges into Spirit: E. M. Forster’s Alexandria,” a pleasing

find, and certainly one of the most insightful and engaging essays to ever appear on Mr.

Forster’s book.

William G. Beckford, Publisher

FONTHILL PRESS

New York/Winchester, UK

from the INTRODUCTION

WHERE SENSE VERGES INTO SPIRIT:

E. M. FORSTER’S ALEXANDRIA

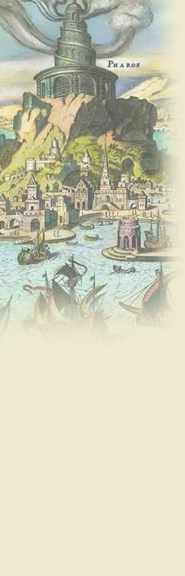

Homer tells how Menelaus was becalmed on Pharos as he returned from Troy, and how he

could not get away until he had entrapped Proteus, the divine king of the island, and exacted

a favorable wind (see opening passages of Forster’, Alexandria).

Age cannot wither her. Cleopatra, twenty centuries past her prime, continues to attract

us. In the central chapter of Alexandria: A History and a Guide, E. M. Forster declares himself

another votary of this last great representative of the dynasty that stretches, “like a rare and

fragile chain,” backward to Alexander. A close look at Forster’s Cleopatra may allow readers

to see a neglected text with fresh eyes, to recognize it as an imaginative work of no small

consequence, and even to descry an uncanny anticipation of the postcolonial perspectives

that, by century’s end, would complicate our understanding of subject populations and their

female exemplars…

In his meditation on Egypt’s great queen and her city, Forster compels recognition of

the essential schizophrenia of expatriation across its full spectrum, from tourism to

colonialism. The schizophrenia begins with the title, for Forster’s book purports to situate

Alexandria in time and to describe it in space—to be history and guide. Both of the terms in

this binary exhibit their own sublevel fissuring. The first term, history, may beckon with the

promise of linear unity, but it always breaks down into Eliot’s many cunning passages. The

second term is equally vexed: who is to be guided? The tourist? The antiquary? The colonial

official? Can the would-be cicerone find a voice suited to every visitor? History notoriously

is his story and our story, seldom her story or their story. In Alexandria of all places there are

in the house of history many mansions—at least one for every empire that has laid claim to this corner of the Mediterranean. Struggling to write history from an Alexandrian vantage

(and in one crucial chapter from the perspective of the city’s most famous indigenous

queen), a twentieth-century Englishman faces a daunting task.

One sees a basic division in the very activity that requires a guide. Is one to be a traveler

or a tourist? According to the classic distinction, travelers seek to encounter foreign

experience in as much depth and authenticity as possible; mere tourists, on the other hand,

seek to take their familiar world with them, wanting a sterile envelope from which to marvel

at the doubtless septic sights of Abroad. Thus the author of such a text, the guide who writes

the guidebook, must often strike a precarious balance between counseling tourists on how to

live as though they were at home and counseling the traveler on how to live like a native…

* David Cowart’s “Where Sense Verges into Spirit: Forster’s Alexandria ” originally appeared in a slightly

different version in the Michigan Quarterly Review.

DAVID COWART

Lousie Fry Scudder Professor

English Language and Literature

University of South Carolina

|

Back in Alexandria again, [Cleopatra] watched the second duel—that between Mark Antony and Caesar’s murderers. She helped neither party, and when Antony won he summoned her... She came,

not in a carpet but in a gilded barge, and her life henceforward belongs less to history than to poetry...

Voluptuous but watchful, she treated her new lover as she had treated her old. She never bored him,

and since grossness means monotony she sharpened his mind to those more delicate delights, where

sense verges into spirit. Her infinite variety lay in that. She was the last of a secluded and subtle race,

she was a flower that Alexandria had taken three hundred years to produce and that eternity cannot

wither.

Back in Alexandria again, [Cleopatra] watched the second duel—that between Mark Antony and Caesar’s murderers. She helped neither party, and when Antony won he summoned her... She came,

not in a carpet but in a gilded barge, and her life henceforward belongs less to history than to poetry...

Voluptuous but watchful, she treated her new lover as she had treated her old. She never bored him,

and since grossness means monotony she sharpened his mind to those more delicate delights, where

sense verges into spirit. Her infinite variety lay in that. She was the last of a secluded and subtle race,

she was a flower that Alexandria had taken three hundred years to produce and that eternity cannot

wither.