E.M. Forster’s

ALEXANDRIA:

A HISTORY AND GUIDEThe Romance

of Tristan and Iseult

by Joseph Bédier

and Hilaire BelloIn The Fullness of Time

by Vincent NicolosiThe Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff:

I AM THE MOST INTERESTING BOOK OF

ALL & LUST FOR GLORY War in Nicaragua

by William WalkerABOUT FONTHILLCONTACT FONTHILL

|

War in Nicaragua

THE WAR IN NICARAGUA.

CHAPTER FIRST

THE VESTA AND HER PASSENGERS.

ON the 5th of May, 1851, a number of native Nicaraguans, who had been exiled by the existing Government of their Republic, landed at Realejo , and thence proceeded to Chinandega with a view of organizing a revolution against the acting authorities of the country. Among them were D. Maximo Jerez , D. Mateo Pineda, and D. José Maria Valle, leading citizens of the Occidental Department. They had sailed from Tiger Island on a vessel commanded by an American, Gilbert Morton , and were about fifty-four in all when they surprised the garrison at Realejo. After the revolutionists reached Chinandega, they were joined by large numbers of the people, and they proceeded with little delay to their march towards León. On the road thither they met the forces of the Government at several points, each time routing them; and the President, D. Fruto Chamorro, seeing the temper of the people, and unable to resist the revolution about León, fled alone, without an escort, to Granada. He did not reach the last named city for some days after leaving León, having gone astray in the woods and hills about Managua, and his partisans had almost despaired of ever again seeing him, when he rode into the town where his principal adherents resided.

After the revolutionists, headed by Jerez, reached León, they organized a Provisional Government, naming as Director, D. Francisco Castellón . This gentleman had been a candidate for the office of Director at the preceding election in 1853; and his friends asserted that he had a majority of votes, but that Chamorro had obtained the office by the free use of bribes among the members of the electoral college. Chamorro was installed in the office, and soon found pretexts for banishing Castellón and his chief supporters to Honduras. In that State, General Trinidad Cabañas held executive power; and favored by him, Jerez and his comrades had been able to sail from Tiger Island with the arms and ammunition requisite for their landing at Realejo .

While his political enemies were in Honduras, Chamorro had called a constituent Assembly, and the constitution of the country had been thoroughly revised and changed. The constitution of 1838 placed the Chief Executive power in the hands of a Supreme Director, who was elected every two years; the new constitution created the office of President, who was to be chosen every four years. In all respects the new constitution placed more power in the Government than had been trusted to it by the previous law; hence it was odious to the party styling itself Liberal, and acceptable to those who called themselves the party of order. The new constitution was printed on the 30th of April, 1854; and its partisans say it was also promulgated on that day. The opponents of the new constitution say it never was promulgated. At any rate, the revolution made professedly against this constitution, was started on the 5th of May, before the new law could have been announced in the towns and villages distant from the capital.

The Leónese revolutionists styled their Executive Provisional Director, and asserted their resolution to maintain the organic act of 1838. They took the name of Democrats, and wore as their badge a red ribbon on their hats. Chamorro was called by his friends President—they thus declaring their adhesion to the new constitution; and calling themselves Legitimists, they mounted the white ribbon, in opposition to the red of the Democrats.

During the month of May the Provisional Government was accepted by all the municipalities of the Occidental Department, and by some of the other towns; and the democratic army, as it was called, marching southward, reached Granada in the early part of June. The delay of the Democrats at León and at Managua had given Chamorro time to organize force, and though his numbers were small, he repulsed Jerez and his followers (for these latter could not be called a force) when they attempted to carry Granada by assault. After the first repulse, Jerez sat down before the town, and affected to lay siege to the place. The rabble at his heels were, however, busier in plundering the shops of the suburbs than in defeating the plans of their enemies. The arrival of some officers and soldiers from Honduras assisted Jerez in his efforts to organize the “democratic army,” and was a proof of the readiness with which Cabañas had recognized the provisional Government

For some months Jerez remained at Granada, vainly attempting to gain possession of the chief square of the city, known as the Plaza. All the towns of the State had in the meanwhile declared for Castellón, and his friends held the lakes as well as the San Juan River , by means of small schooners and bungos . The schooners were under the command of a physician—an American or Englishman who had resided in the United States, and bore the name of Segur, although his real name was Desmond. In the month of January, 1855, Corral succeeded in taking Castillo, as well as the lake schooners, from the Democrats; and soon thereafter Jerez broke up his camp before Granada and retreated in a rapid and disorderly manner towards Managua and León. The flight of the Democrats from Rivas followed almost immediately the retreat from Granada; and in a few weeks the turn of affairs was visible by the adhesion of many persons of property to the Legitimist party.

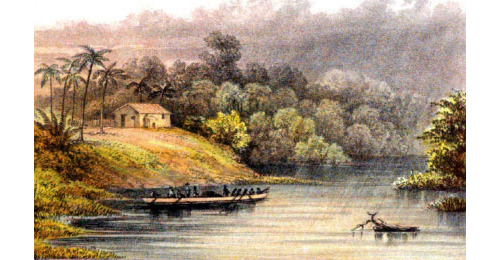

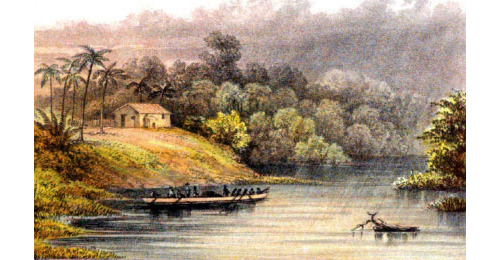

Bungo

It was well for the Democrats that Chamorro, worn out by long disease and anxious thought, died a short time after they left the Jalteva . He was buried in the parish church, on the main Plaza of Granada, and his death, was kept carefully concealed from the enemy. His name was strength to the Legitimists and a terror to their foes; had he lived, a far more vigorous hand than that of Corral would have driven the flying Democrats back to the square of León. After the death of Chamorro, Corral remained in command of the Legitimist army, and the Presidency fell, under the constitution of 1854, to one of the Senators, D. José Maria Estrada .

In the meantime, causes at work outside of Nicaragua were destined to influence very materially the fate of the Provisional Government. President Carrera, of Guatemala, being friendly to the principles of the party led by his countryman Chamorro, had determined to act against the Government of Cabañas, in Honduras. In view of this fact, Alvarez and the Honduras contingent received orders to return from Nicaragua, and this dampened the spirit of the Democratic leaders. Honduras, threatened by the much greater power of Guatemala on the north, not only had need of all the resources she could control, but she could hardly hope, without foreign assistance, to resist the strength of Carrera and his Indians. Not even the Nicaraguans themselves could blame Cabañas for the course he took, and the friendship between Castellón and the President of Honduras remained unaffected by the policy the latter was forced to pursue. The alliance between the Governments at León and at Comayagua continued, and they seemed to be linked together for common fate. But closely as the cause of Castellón was bound to that of Cabañas, it was not in Honduras, nor yet in Guatemala, that its destiny was being determined. The very day which witnessed the most single triumph of the Nicaraguan Democrats was destined to behold the overthrow of the Cabaña administration; and to ascertain the cause of such a strange result we must leave Central America and consider events in California.

Three days after Jerez and his comrades landed at Realejo—that is on the 8th of May, 1854—a novel scene was enacted on the boundary between Upper and Lower California. On that day a small band of Americans marched from the Tia Juana country-house to the monument marking the boundary between the United States and Mexico, and there yielded their arms to a military officer of the former power. These men were poorly clad, but even at the moment of their surrender they—I speak not of their leader—bore themselves with a certain courage and dignity not unworthy of men who had aspired to found a new State. They were the last of what has been called the Expedition to Lower California; and some among them had seen the flag of Mexico lowered at La Paz to give place to another made for the occasion. They had passed through much toil and danger; and most of them, being altogether new to war, had taken their first lesson in that difficult art by long fasts and vigils, and marches across one of the most inhospitable regions of the American continent. The natural obstacles of Lower California, the scarce subsistence, the long intervals between watering-places, the rugged sides of the mountains, and the wide wastes of sandy desert, would make war in that territory not a pastime even to a well-appointed force. And when you add to these natural difficulties an enemy who knows the country well, and who is always able to muster larger numbers than your own, some idea may be formed of the trials of those engaged in the Lower California Expedition. When, however, these men crossed the line, they gave no sign of failing spirit, but looked at the foe, which hung about their rear and flanks, with as resolute a face as if they had just left a field of triumphant victory. Such a fact is itself sufficient to prove that the vulgar ideas of this expedition are false; and as several of the persons with Colonel Walker in Lower California afterward acted in Nicaraguan affairs, it is not irrelevant to ascertain the motives which guided them in their enterprise, so little understood by the American people.

The object of these men in leaving California was to reach Sonora; and it was the smallness of their numbers which made them decide to land at La Paz. Thus forced to make Lower California a field of operations until they might gather strength for entering Sonora, they found a political organization in the peninsula requisite. Their leader intended to establish a military colony as soon as possible on the frontier of Sonora—not necessarily a colony hostile to Mexico—but one to protect Sonora from the Apaches. The design of such a colony first took form at Auburn, in Placer County, California, early in 1852. A number of persons there contributed to send two agents to Guaymas for the purpose of getting a grant of land near old town of Arispe, with the condition of protecting frontier from the Indians. These agents—one of whom was Mr. Frederic Emory—arrived in Sonora just after Count Raousset de Boulbon had agreed to settle several hundred French near the mine of Arizona; and State Government of Sonora expected the French to do the work the Americans desired to attempt. Mr. Emory and his companion, therefore, failed in their object; and the Count de Boulbon, soon afterward going to Sonora, the Auburn plan was abandoned. The Government of Arista, or rather persons attached to that administration, became hostile to Raousset de Boulbon on account of their interest in a conflicting claim to the mine he contracted to work; and by the intrigues of Colonel Blanco , the French were driven into revolution, and afterward, during the illness of their leader, into an agreement to leave the country.

At the time the news of their departure from Sonora reached California, Mr. Emory proposed to Mr. Walker, to revive the Auburn enterprise; and Walker, together with his former partner, Mr. Henry P. Watkins, sailed for Guaymas, in the month of June, 1853, intending to visit the Governor of Sonora, and try to get such a grant as might benefit the frontier towns and villages. Walker was careful to provide himself with a passport from the Mexican consul at San Francisco; but this availed him little when he reached Guaymas. The day after his arrival there the Prefect ordered him to the office of police, and after a long examination forbade him to leave for the interior, refusing to countersign his passport for Ures . Seeing the obstacles placed in his way at the outset, Walker determined to return to California; and after he went aboard the vessel for that purpose the Prefect sent him word the Governor, Gandara , had ordered his passport to be countersigned in order that he might go to the capital. The same courier who bore the order from Gandara to the Prefect, Navarre , also brought news that the Apaches had visited a country-house, a few leagues from Guaymas, murdering all the men and children, and carrying the women into a captivity worse than death. The Indians sent word that they would soon visit the town “where water is carried on asses’ backs”—meaning Guaymas; and the people of that port, frightened by the message, seemed ready to receive any one who would give them safety from their savage foe. In fact several of the women of the place urged Walker to repair immediately to California, and bring down enough Americans to keep off the Apaches.

What Walker saw and heard at Guaymas satisfied him that a comparatively small body of Americans might gain a position on the Sonora frontier, and protect the families on the border from the Indians; and such an act would be one of humanity, no less than of justice, whether sanctioned or not by the Mexican Government. The condition of the upper part of Sonora was at that time, and still is, a disgrace to the civilization of the continent; and until a clause in the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgowas rescinded by one in the Gadsden treaty , the people of the United States were more immediately responsible before the world for the Apache outrages. On none more immediately than on the American people, did the duty devolve of relieving the frontier from the cruelties of savage war. Northern Sonora was, in fact, more under the dominion of the Apaches than under the laws of Mexico; and the contributions of the Indians were collected with greater regularity and certainty than the dues to the tax-gatherer. The state of this region furnished the best defense for any American aiming to settle there without the formal consent of Mexico; and although political changes would certainly have followed the establishment of a colony near Arispe, they might he justified by the plea that any social organization, no matter how secured, is preferable to that in which individuals and families are altogether at the mercy of savages.

But the men who sailed for Sonora were obliged to sojourn, for a time, on the peninsula; and their conduct in Lower California may be taken as the measure of their motives in the enterprise they undertook. Wheresoever they went they sought to establish justice and maintain order, and those among them who violated law were summarily punished. An instance occurred at the old mission of San Vincente , illustrative of the character of the expedition, and of the persons who directed it. Several of the soldiers had formed a conspiracy to desert and to pillage the cattle-farms on their way to Upper California. The plan and purposes of the conspirators were revealed by one of the confederates, and the parties to the plot were tried by court-martial, found guilty of the charge, and sentenced to be shot. A military execution is a good test of military discipline; for no duty is so repulsive to the soldier as that of taking life from the comrade who has shared the perils and privations of his arduous service. On this occasion, too, the duty was more difficult, because the number of Americans was small, and was daily diminishing. But painful as was the duty, the men charged with the execution did not shrink from the performance of it; and the very field where the unfortunate victims of the law expiated their offence with their lives, was suggestive of comparison between the manner in which the expeditionists—and the Mexican Government severally performed the duties of protection to society. The expeditionary force, drawn up to vindicate law, by the most serious punishment it metes out to the offender, stood almost in the shadow of the ruins of the church of the mission fathers. The roofless buildings of the old monastery, the crumbling arches of the spacious chapel, the waste fields which showed signs of former culture, and the skulking form of the half-clothed Indian, relapsing into savageism from which the holy fathers had rescued him, all declared the sort of protection Mexico had given to the persons as well as the property of the Peninsula. In the vital functions of government, the expeditionists may safely challenge a comparison of their acts with those of Mexico in Lower California; and the ruin and desolation which followed the unwise no less than unjust measure of secularizing the missions, were sufficient to forfeit the claim of the Mexican Republic to the allegiance of the peninsula.

The main fact for us to know is that those engaged in the Lower California expedition gave proof of their desire not to destroy, but to re-organize society wherever they went. They were all young men, and youth is apt to err in pulling down before it is ready to build up. But they were men, also, full of military fire and thirsting for military reputation; and the soldier’s instinct leads him to construct rather destroy. The spirit of the soldier is conservative; the first law of military organization is order. Therefore, these men, though young, were not ill-fitted to lay the foundations of a new and more stable society than any might find either in Sonora or Lower California. They failed, however; whether through the actions of others more than of themselves, it imports not our present purpose to determine. Suffice it to say that the last remains of the expedition reached San Francisco about the middle of May, 1854.

The leader of the expedition—William Walker, or, as he was then called, Col. Walker—after returning to Upper California, resumed the occupation of editor of a daily paper. One of the proprietors of the paper he edited was Byron Cole, whose attention had been for several years directed to Central America, and more particularly to Nicaragua. Cole, in frequent conversations with Walker, urged him to give up the idea of settling in Sonora, and devote his labors to Nicaragua; and soon after he heard of the revolution undertaken by Jerez and Castellón, Cole sold his interest in the paper at San Francisco, and sailed for San Juan del Sur. He left for Nicaragua on the steamer of the 15th of August, 1854, being accompanied by Mr. Wm. V. Wells , whose attention was fixed on Honduras. From San Juan del Sur, Mr. Cole, after numerous delays and vexations, succeeded in getting to León, and there obtained from Castellón a contract, by which the Provisional Director authorized him to engage the services of three hundred men for military duty in Nicaragua, the officers and soldiers to receive a stated monthly pay, and a certain number of acres of land at the close of the campaign. With this contract Cole returned to California early in the month of November, and forthwith sought Walker for the purpose of getting him to take an interest in the enterprise. As soon as Walker read the contract he refused to act under it, seeing that it was contrary to the act of Congress of 1818, commonly known as the neutrality law . He, however, told Cole that if he would return to Nicaragua, and get from Castellón a contract of colonization something might be done with it. Cole accordingly sailed a second time for San Juan; and on the 29th of December, 1854, Castellón gave him a colonization grant, under which three hundred Americans were to be introduced into Nicaragua, and were to be guaranteed forever the privilege of bearing arms. This grant Cole sent to Walker, and it reached the latter at Sacramento early in the month of February, 1855.

A few days after receiving this contract, Walker traveled to San Francisco with the view of providing means, if possible, for carrying two or three hundred men to Nicaragua. He met there met an old schoolmate, Mr. Henry A. Crabb , who had just returned from the Atlantic States; and Crabb having passed through Nicaragua on his way from California to Cincinnati, gave a glowing report of the natural wealth and advantages of the country. While crossing the Transit Road , Crabb heard of the events then transpiring in the Republic—of the revolution at León and the siege of Granada; he also ascertained that Jerez was anxious to obtain the aid of Americans for the campaign against the Legitimists. This suggested the idea of getting an element into the society of Nicaragua for the regeneration of that part of Central America ; and while in the Atlantic States Crabb had secured the co-operation of Mr. Thomas F. Fisher , formerly and now of New-Orleans, and of Captain C. C. Hornsby , who had served in one of the regiments known as the Ten Regiments , during the Mexican war. The three, Crabb, Fisher, and Hornsby, left New-Orleans together in the month of January, 1855: and on the way to San Juan del Norte they found aboard the steamer Mr. Julius DeBrissot , bound, as he said, for the Galapagos Islands. DeBrissot joined the party; and he, together with Hornsby and Fisher, remained in Nicaragua, while Crabb proceeded to San Francisco. When Walker met Crabb at the latter place, he was awaiting advices from Fisher, who stopped on the Isthmus for the purpose of visiting Jerez and obtaining from him authority to engage Americans for the service of the Democratic army.

Not many days elapsed before Fisher came to California, bringing with him authority to enlist five hundred men for Jerez, and with a promise of the most extravagant pay, in both money and lands, to the officers and men who might engage in the service. It seems Fisher, Hornsby, and DeBrissot, found the newly-arrived United States Minister, John H. Wheeler , on the Isthmus; and as His Excellency was anxious to visit the Democratic camp in the Jalteva, as well as Chamorro, in Granada, before deciding what authority he would recognize, Fisher and his party went as an escort to the Minister, and under the protection of the American flag, into both camps. From Jerez, however, Fisher obtained at this time the contract he bore to San Francisco; while Hornsby and DeBrissot, after leaving Granada, went to Rivas, and entered into a Quixotic agreement with D. Maximo Espinosa to take Fort Castillo Viejo and the San Juan River from the Legitimists, who had lately driven the Democrats from the stronghold the Rapids. These two gentlemen, however, were soon glad to manage their escape from San Juan del Sur aboard the steamer for San Francisco; and not long after Fisher’s arrival, Hornsby and DeBrissot both appeared in California.

Just below the rapids of el Rio San Juan.

Crabb and Walker had known each other from childhood, and their views were similar in regard to the state of Central America, and the means necessary for its regeneration. Therefore, Crabb generously proposed to give Walker the whole benefit of the contract Fisher had made with Jerez; and Crabb, in view of certain political movements then occurring in California decided to remain in that State. Walker, however, while thanking Crabb for his offer, refused to have anything to do with the Jerez contract, preferring to act under the Castellón grant to Cole, not only because of its entire freedom from legal objections, but also because it was more reasonable, and had been given by an authority competent to make the bargain. Hornsby and DeBrissot embarked in the enterprise with Walker; and it will be seen hereafter that they, as well as Fisher, held commissions under the Republic of Nicaragua.

In the meanwhile, Walker had taken care that no show of secrecy should bring suspicion on his undertaking, either as to its illegality or its injustice. He took the Cole grant to the District Attorney of the United States for the Northern District of California, Hon. S. W. Inge, and that gentleman after examining it declared no law would be violated by acting under it. At that time, too, General Wool , commanding the Pacific Division, was supposed to have special power from the President for suppressing expeditions contrary to the Act of 1818 . His headquarters were at Benicia, and the General was in the habit of reading to many persons the letters addressed by him to the then Secretary of War, Colonel Jefferson Davis, defending the course he took in reference to the Lower California expedition. Among others, he read these letters (which the old gentleman seemed to think of models of logic and style) to Walker, the very person about whose acts the discussion had arisen between himself and the Secretary. From these letters Walker was led to infer that the common impression about the powers vested in the General, under the Act of 1818, was correct; and, therefore, when he heard of General Wool being in San Francisco, he sought him out, and found him on the wharf only a few minutes before four o’clock, the hour for the departure of the Sacramento steamer. The General was about to leave in the boat for Benicia; and after hearing Walker’s statement as to the nature of the grant made to Cole, and of his intention to act under it, the old man, shaking him heartily by the hand, said he not only would not interfere with the enterprise, but wished it entire success. Thus having secured the sanction of the proper Federal authorities, Walker proceeded in his efforts to provide means for carrying colonists to Nicaragua under the Cole contract. He soon found that it would be impossible to get more than a pitiful sum of money, and that his arrangements would have to be made on the most economical scale.

While engaged in these preliminary preparations, Walker received an injury in the foot , which kept him in his chamber until the middle of April; and, in fact, the sore was not wholly healed when he sailed from San Francisco. Thus confined to the house, he was able to do little more in the way of means than to obtain a thousand dollars from Mr. Joseph Palmer, of the firm Palmer, Cook & Co. At this gentleman’s house he had met with Colonel Fremont and talked with him about the enterprise in Nicaragua; and the Colonel, who had passed across the Isthmus the previous year, thought well of the undertaking . It is due probably, to both Colonel Fremont and Mr. Palmer, to state that they were not fully aware of all the views Walker held on the subject of slavery; nor, indeed, was it necessary at that time for those views to be expressed. Besides the assistance given by Mr. Palmer, Walker was much aided by two friends—Mr. Edmund Randolph and Mr. A. P. Crittenden.

After much difficulty, a contract was made with one Lamson for the passage of a certain number of men, aboard the brig Vesta, from San Francisco to Realejo. The agreement had been made through a shipmaster, McNair, and it was considered that he would sail in command of the Vesta. But, after the cash payment on the charter party had been made to Lamson, he and McNair fell out, and the former was obliged to employ another captain for his vessel. The provisions and the passengers were all aboard the brig about the 20th of April; when it was thought she was on the point of leaving, the Sheriff seized the vessel by attachment at the suit of an old creditor of the owner, Lamson. The evening, too, after the attachment, there were some signs of the brig getting under way for sea; and therefore the Sheriff sent down a posse of eight or ten, armed with revolvers, for the purpose of preventing an escape.

A sort of scuffle, more in jest than in earnest, occurred between some of the posse and their acquaintances among the passengers; and the new captain, frightened out of his wits, jumped over the rail to the wharf, taking with him the papers of the ship. A few days afterward the United States Marshal served a writ on the brig for the price of the provisions; and the revenue cutter W. L. Marcy was hauled astern of the Vesta, with orders to keep her from going to sea with the Deputy Marshal aboard. To make assurance doubly sure, the Sheriff had the sails of the brig unbent and put in store. The owner seemed to be entirely without means to satisfy the claims against the vessel, and everybody thought the chance very small for the departure of the vessel on her proposed voyage.

Walker, however advised the passengers to remain aboard, and all except a few followed the advice. Soon he found a captain for the Vesta, in the person of Mr. M. D. Eyre, who professed some knowledge of navigation. The holder of the claim against Lamson, under which the attachment issued, happened to be a friend of Crabb, from Stockton ; and he was induced by good will for the voyage the Vesta was bound on, to grant easy terms for the release of the brig. Lamson really controlled the action of the merchants who sold him the provisions; and when he was told it might not be safe for him to keep the passengers in San Francisco, he rather hesitatingly agreed to have the libel dismissed. But the sheriff’s costs had run up, by the employment of the posse, and other extraordinary expenses, to more than three hundred dollars; and Walker having expended nearly the last dollar, it seemed as if this trivial amour might stop the whole enterprise. The costs of the sheriff were very large, if not illegal; but, as he had the sails in store, he seemed to have the Vesta in his power. Walker managed, however, to get an order from the sheriff on the storekeeper for the sails; and as the sheriff was kept in ignorance of the dismissal of the libel, he supposed the cutter would detain the brig in port if she tried to get out. Besides this, he had a keeper aboard; and the keeper having been a member of a California Legislature, was supposed to keep a sharp lookout for any suspicious movement. The captain of the cutter was informed a little before dark that the Vesta was out of the marshal’s hands, and arrangements were made through one of the Marcy’s officers, for her sailors to come aboard about ten o’clock, in order to bend the sails of the brig. The United States sailors came at the appointed time, and the passengers managed to get the sheriff’s keeper into the cabin, where he was detained for several hours. Swiftly and silently the work of bending the sails went on; and shortly after midnight, on the morning of the 4th of May, 1855, the steam-tug Resolute came alongside the Vesta, and hitching her on, towed her from the wharf, through the shipping, into the stream, and out by the Heads to sea. The sheriff’s keeper was sent to the Resolute, the towlines were cast off, and the Vesta put to sea, to the great joy of the passengers, who had been for two weeks alternating between hope of her departure and fear of her detention.

When the brig got to sea, it was found that there were fifty-eight passengers bound for a new home in the tropics. Among them were Achilles Kewen , who had commanded a company under López, at Cardenas, in 1850 ; Timothy Crocker , who had served under Walker throughout the Lower California expedition; C. C. Hornsby, whose previous adventures in Nicaragua have been alluded to; Dr. Alex Jones, who had lately been to the Cocos Islands in search of a buried treasure ; Francis P. Anderson, who had served in the New-York regiment in California during the Mexican war; and others, whose names will hereafter appear in the course of this narrative. They were most of them men of strong character tired of the humdrum of common life, and ready for a career which might bring them the sweets of adventure or the rewards of fame. Their acts will afford the best measure both of their capacity and of their character.

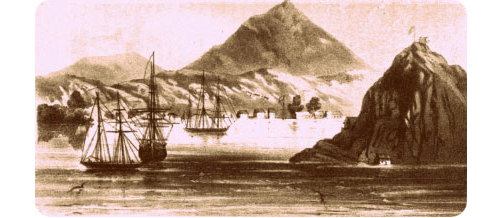

The voyage of the Vesta was rather long and tedious. In crossing the Gulf of Tehuantepec she encountered a gale which tested her timbers—twenty-nine years in her sides—to the utmost. The bow of the old brig would open to the waves as they roared around her, and at times her decks were swept clear by huge billows passing over her. She was worked by men detailed from the passengers; and after living through the storm off Tehuantepec, the crew had little to do until she reached the Gulf of Fonseca. More than five weeks had been consumed since leaving San Francisco before the volcano of Coseguina —the first Nicaraguan land—was seen looming in the distance. The want of wind detained the brig for some hours at the mouth of the gulf, while a boat was sent in to the port of Amapala, on the Island of Tigre. Captain Morton, the same American who had carried Jerez to Realejo, in May, 1854, was at Amapala with instructions from Castellón, awaiting the arrival of the Vesta. The captain was gladly welcomed aboard the brig, as the skipper who had brought the vessel from San Francisco knew nothing of the Central American coast. After taking Morton aboard, the Vesta proceeded on her way, and on the morning of the 16th of June, she came to anchor within the port of Realejo.

Island of Tigre

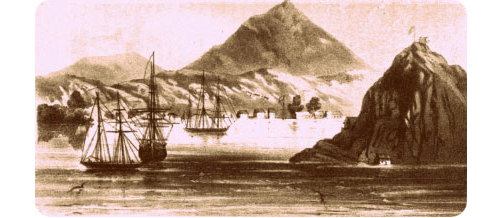

Port of Realejo, USS Merrimack

I have been somewhat minute, and it may be tedious, in narrating the earlier incidents of the enterprise whereby Americans were introduced as an element into Nicaraguan society, because we may often judge best of events by clearly seeing their origin. The father ceases to have any direct influence over either the mind or the organization of the child after the moment of conception; and yet how often we trace not merely the features of the father, but even the delicate traits of his character, in his offspring. The fine cells which determine the nature of organic structure have been minutely studied by the physiologist, and the manner of their development has opened to him some of the hitherto hidden laws of life. If, then, you desire to understand the character of the late war in Nicaragua, do not despise the small events which attended the departure of the fifty-eight from San Francisco. From the day the Americans landed at Realejo dates a new epoch, not only for Nicaragua, but for all Central America. Thenceforth it was impossible for the worn-out society of those countries to evade or escape the changes the new elements were to work in their domestic as well as in their political organization.

The state of native parties in Nicaragua on the 16th day of June, 1855, was quite different from that existing on the 29th of December, 1854—the day on which Castellón made the grant to Cole. When the Vesta dropped anchor in the port of Realejo, the Provisional Government was confined almost entirely to the Occidental Department . The Legitimists held all the Oriental and Meridional Departments, and most of the towns and villages in Matagalpa and Segovia were subject to their sway. The ally, too, of the Provisional Government, Cabañas, sat less firmly in the executive chair of Honduras than he had on the previous Christmas. A force organized by the aid of Guatemala, and commanded by a General Lopez , had invaded the Department of Gracias; and while Lopez was sent into the north of Honduras, General Santos Guardiola—whose name was itself a terror to the towns of both States—sailed from Istapa for San Juan del Sur, aboard the Costa Rican schooner San José, with the intention of engaging in the service of the Legitimists for a campaign in Segovia, close to the confines of Tegucigalpa and Choluteca. Guardiola arrived at Granada only a few days before Walker reached Realejo; and the latter found the people about Chinandega trembling at the name of one who—whether properly or improperly it is hard to say—had acquired the epithet of the “Butcher” of Central America. After the retreat from Granada Jerez had fallen into disgrace with his party—at least they denied him all claim to military capacity, no doubt glad to place on the shoulders of their leader the blame of all the misfortunes which had followed their entire want of military virtue. In place of Jerez, Castellón put at the head of the “Democratic Army” General Muñoz , who had that time more reputation as a soldier than any man in Central America. He had been invited to León from Honduras, whither he had retired several years previously in consequence of having failed in a revolution against the Government of D. Laureano Pineda ; and it was only by much entreaty and grave concession that Castellón had prevailed upon him to take the command of the army of the Provisional Government. Since assuming the command Muñoz had acted wholly on the defensive devoting his time to drilling the men pressed into the service of Castellón; and it was widely whispered among the people, especially among the blood reds of the Democrats, that Muñoz was anxious for a compromise between the two contending parties, thinking more of maintaining himself in power than of the success of the principles for which the revolution was begun.

|